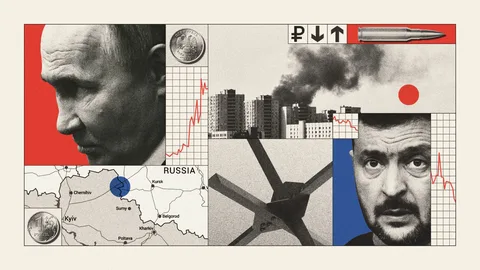

Russia’s Wartime Economy Falters Amid Sanctions and Structural Strains

Russia’s economy, once touted by the Kremlin as resilient against Western pressure, is showing increasing signs of strain as the war in Ukraine drags into its third year. Despite a wartime boom in military production and state subsidies, sanctions, labor shortages, and structural inefficiencies are beginning to take a toll, raising questions about the sustainability of Moscow’s economic strategy.

A Sanctions-Battered System

Western sanctions have targeted Russia’s financial sector, energy exports, and access to advanced technology. While Moscow has managed to redirect some of its oil and gas sales to Asia—particularly China and India—the shift has come at a steep cost. Russia is selling crude at a discount, cutting deeply into revenues that once formed the backbone of the national budget.

The ruble has also endured repeated bouts of volatility, forcing the central bank to raise interest rates to levels not seen in years. Inflation, particularly in food and consumer goods, has eroded household purchasing power. While official figures paint a picture of modest growth, independent economists warn that the numbers are propped up by extraordinary wartime spending rather than real productivity gains.

Military Keynesianism, Russian Style

At the heart of Russia’s economic survival strategy has been a surge in defense spending. Factories once producing civilian goods have been retooled to churn out tanks, shells, and drones. This wartime mobilization has kept industrial output high and unemployment low, but at the cost of distorting the broader economy.

The defense sector’s dominance has led to shortages in skilled labor and raw materials for other industries. Civilian infrastructure projects are being delayed, and consumer-facing businesses—from retail to hospitality—report sluggish demand. Economists warn that Russia is becoming increasingly dependent on a “military Keynesian” model, where state-driven defense orders create the illusion of growth while hollowing out long-term potential.

Labor Shortages and Demographic Pressures

Another structural challenge is the workforce. Hundreds of thousands of young Russians have fled abroad since the invasion began, seeking to avoid mobilization or build new lives in Europe, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. At the same time, casualties on the battlefield have thinned the ranks of working-age men, leaving industries scrambling to fill positions.

Employers are now offering higher wages and benefits to attract workers, driving up labor costs and adding to inflationary pressures. The Kremlin has turned increasingly to migrants from Central Asia to plug the gaps, but anti-immigrant sentiment and bureaucratic hurdles have complicated these efforts.

Import Substitution Struggles

One of Moscow’s central responses to sanctions has been its policy of “import substitution,” aimed at replacing Western technology and goods with domestic alternatives or supplies from friendly countries. In some areas, such as agriculture, the policy has delivered results. But in high-tech sectors—particularly semiconductors, aviation, and advanced machinery—progress has been limited.

Russian airlines, for example, are keeping aging fleets in the air by cannibalizing parts and relying on gray-market imports. The automotive sector has also been hit hard, with production slumping and consumers facing fewer options and higher prices. Even in energy, where Russia remains a global player, sanctions on equipment and investment are curbing the ability to develop new projects.

A Growing Fiscal Burden

The costs of sustaining the war are weighing heavily on Russia’s finances. Defense spending now accounts for more than a third of the federal budget, crowding out investment in healthcare, education, and infrastructure. To cover deficits, the government has leaned on increased taxation of energy companies and withdrawals from its sovereign wealth fund.

While these measures have provided short-term relief, they raise concerns about long-term sustainability. Analysts warn that if energy revenues continue to fall, Russia may be forced to cut spending or resort to more aggressive borrowing, which could destabilize financial markets.

The Geopolitical Dimension

Russia’s economic struggles are not just domestic but geopolitical. Reliance on China and India as key markets and suppliers has deepened Moscow’s dependence on partners whose support is transactional rather than ideological. Beijing, in particular, has secured favorable terms in energy deals and expanded its influence over Russian trade and finance.

This shift risks reducing Russia to a junior partner in its relationship with China, limiting Moscow’s leverage even as it tries to project strength abroad. Meanwhile, European markets—the most lucrative for Russian energy—remain largely closed, and prospects for normalization appear dim.

Conclusion

The Kremlin continues to project confidence, pointing to stable employment figures and strong industrial output as evidence of resilience. But beneath the surface, Russia’s wartime economy is increasingly fragile, held together by extraordinary state spending, discounted exports, and an overstretched workforce.

Sanctions, structural weaknesses, and the costs of prolonged conflict are converging into a perfect storm that could erode Moscow’s ability to sustain its military and social commitments. The longer the war drags on, the more difficult it will be for Russia to maintain the facade of stability.